Learning Experience Designer (LXD)

Lucas Longo

v.1, Feb 27, 2016

“In spite of the proliferation of online learning, creating online courses can still evoke a good deal of frustration, negativity, and wariness in those who need to create them.” – Vai, M. & Sosulski, K. (2015)

ABSTRACT

The trend towards online learning environments is irreversible and an increasing number of higher educational institutions are going in that direction. It is a labor intensive task for professors who must transition from a traditional classroom or lecture hall model to an online environment. Aside from the learning curve into any e-learning authoring tool or learning management systems (LMS) such as Moodle, OpenEdX, Coursera, and Udemy, new content must be created and organized: pdfs, images, videos, links, and animations to list a few. The challenge is to make it easier for professors or subject matter experts (the user) who, for the most part, do not have formal pedagogical training or multimedia content creation skills to publish their courses adopting research-based best-practices.

Learning Experience Designer (LXD) embeds curriculum construction techniques, tips, guides, and content within the usually blank template you are presented with. It utilizes research-based heuristics to suggest course formats, pedagogical strategies, learner activities, assessments and challenges. During the process of creating a course, LXD will prompt the user for information as well as analyze the content created in real-time to suggest what the next steps could be. Instead of taking a “course on how to create a course on platform X”, LXD integrates this course into the content publishing tool making it a seamless, more pleasing, and easier experience for the user.

As a proof-of-concept, I propose to utilize as a base, an existing LMS and add onto its interface a virtual student / coach that interacts with the user throughout the course creation process. It will start off by asking the user what the course goals and learning objectives are. It will also provide examples, analogies, and recommended steps to develop them. It might recommend assessment points after the user created a certain number of content modules. It will also suggest content for further reading, links to the learning communities or social networks for extended feedback. The idea is to emulate an expert teacher, posing as a student, who is asking guiding questions and providing insights throughout the process of planning the course, creating the content, organizing the learning progression, and creating a learning community with the students.�

CHALLENGE

Needs

In 2009 I started a mobile app development school in Brazil targeting developers and designers who needed to acquire these new hot skills. For the first year or so I taught the iPhone app development course while looking for more teachers to meet the large demand. Pedagogically, I was going on instincts, using a very hands-on approach: explain the concept, model it, and have the students do it themselves. I presented the content through guiding slides and shared my screen when demonstrating. There was no assessment activities except for walking around the classroom making sure everyone was able to copy the modeled activity. The students seemed to enjoy it and it was straightforward enough to explain to new teachers.

The challenge came when I decided I to start selling the courses online. A ‘real’ curriculum had to be designed and new written and video content had to be created. This task proved to be daunting for me and the developers who had no guidelines as to what works or not. The developer-now-teachers were slow to produce the material, and it was usually of poor quality: slides with too many details, missing or confusing explanations of key concepts, badly sequenced, amongst other quality issues. How could I give them guidance as to what quality material looks like? Where do I start? How much video versus written material should I use? How will students ask questions? How will we manage all these students? What are the best practices? All questions that could be resolved by a well designed software that would scaffold the process of creating the curriculum and course content.

Most LMSs offer a “course on how to create a course” yet only provide a blank template with you hit the “new course” button. The need is to have an in-line guide of the steps needed to plan, create, and manage the course. LDX should be adaptable to the user’s interactions and level of expertise as to what questions, scaffolds and suggestions it makes. A user would be exposed to more frequent interventions at the start of the process. The interventions would gradually become less intrusive, yet always available.

LEARNING

Benefits:

LDX will make the user more proficient in the art of sharing their knowledge, stimulating them to repeat the process, and create new and better courses. Users will benefit from theory grounded strategies that promote effective learning in online environments. The virtual student will lead the process by posing provocative questions and requesting content, assessment, and reflection activities to be inserted into the course progression.

The main learning outcome will be that online teaching requires a different set of approaches, content, media, interactive experiences, and assessment methods to be effective. The virtual student will serve as an instructor and coach for the user during the process. Teaching and learning will occur during the process of creating a course.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of LDX I propose to survey the users pre- and post-utilization of the tool with questions that will inform me of the following characteristics of the user:

Pre-utilization:

- Previous knowledge/experience with pedagogy

- Previous knowledge/experience with online teaching

- Perception of online course effectiveness

- Personal beliefs on the challenges of creating an online course

- Confidence level for creating an online course

Post-utilization:

- New pedagogical content acquired

- New online teaching content acquired

- Perception of online course effectiveness

- Personal beliefs on the challenges of creating an online course

- Confidence level for creating an online course

During the utilization of the tool I intend to collect the following data:

- Webcam video recording

- Screen video recording w/ mouse tracks and clicks

- User will be asked to think-aloud throughout the process

I also intend to test LDX with users who have already created online courses and interview them to get the following:

- Perception of how much LDX actually helped them in the process

- What would they do different now if they were to redo their existing courses

- Input and feedback on what worked, what didn’t work, and suggestions

The results will be interpreted using the grounded theory qualitative research method. Theories of how to improve the tool will emerge from the evidence coding and proposition creation. The conclusion will address issues such as the viability of the concept, effectiveness, and suggestions for future improvement.

Approach for Learning:

The approach to learning that informs my design is a combination of the Protégé Effect, Understanding by Design, and TPACK.

The Protege Effect posits that students make a greater effort to learn in the benefit of someone else rather than for themselves, and thus end up learning more in the process of teaching someone else (Chase, Chin, Oppezzo, & Schwartz, 2009). This effect will be elicited through the virtual student who will prompt the user to teach him by asking leading questions, making suggestions, and warning the user about excessive use of one style of teaching as well as the lack of content, reflection opportunities, or detailing of previous knowledge. The virtual student closes the gap between the content ideation and the actual student’s experience. Through immediate feedback, the virtual student will elicit the user to think deeply about content choices and aid in the process of deciding the learning progression that must be in place.

Understanding by Design is a methodology (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) that anchors the curriculum construction process on the end learning goals and evidences of learning. The virtual student’s interactions will guide the user through these steps which provide a structure and sequence that ultimately produces a more cohesive and effective learning experience. By starting with what the student will end up with in terms of knowledge, skills, or understandings, the user will be focused on a clear end goal thus producing better directed content.

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) is a framework that builds on Lee Shulman’s construct of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) to include technology knowledge (Koehler & Mishra, 2009). LDX aims to act precisely within this space insofar as it integrates the complex interaction among three bodies of knowledge: content, pedagogy, and technology. LDX “produces the types of flexible knowledge needed to successfully integrate technology use into teaching.” (Koehler & Mishra, 2009)

DESIGN OF THE LEARNING EXPERIENCE

Existing solutions (“competition”):

LXD is a construct that, for the purposes of this project, will build upon an existing LMS avoiding the enormous task of creating from scratch an entire system to handle content and course organization. It will also build upon the existing “course on creating a course”, which is in effect the main competition of the platform. Users might rather go through such a course and then plan out and publish their own course, without any intrusion from the virtual student. With this in mind, the goal of LDX is to test if such an integration or synchronicity of learning and doing is effective.

Most LMSs offer, within their course creation templates, simple text fields or spaces to fill out the learning objective for each section or lesson for example. LDX takes it a step further by providing leading questions and best practices for each step of the process. It also introduces adaptive feedback based on the content already published on the platform. LDX proposes to analyze the content, media types, and sequence of activities in order to suggest what the user might do next.

Looking at Udemy for example, I’ve found several areas/content that aim at helping the user through the process, yet they are always clearly external to to content publication area. These external areas provide further readings, suggestions, and helpful tips yet they are static in nature.

- Automatic Messages

- Welcome Message

- Congratulations Message

- Course Goals

- Intended Audience

- Course Requirements

- Instructional Level

- Course Summary

Approach for Design:

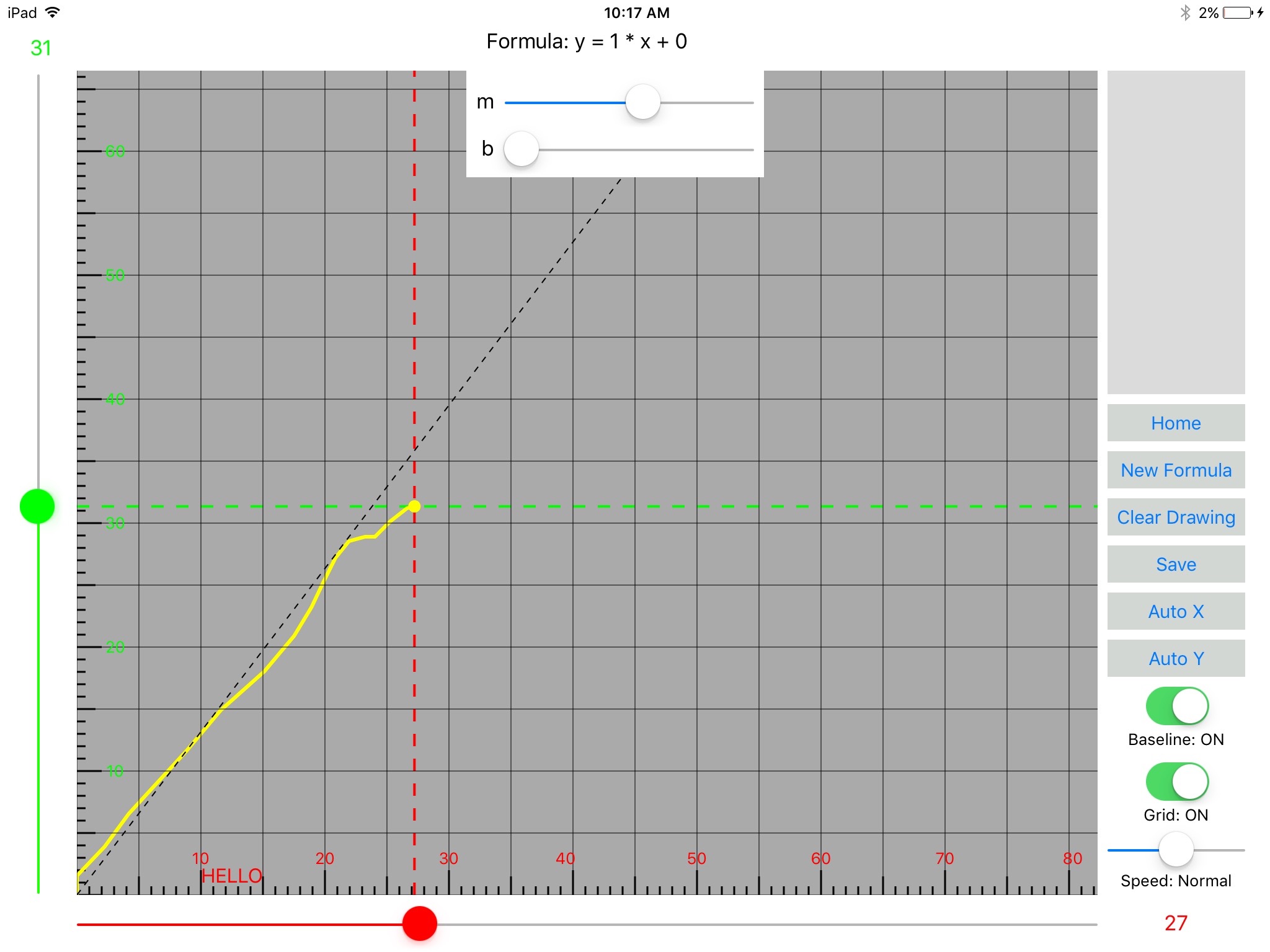

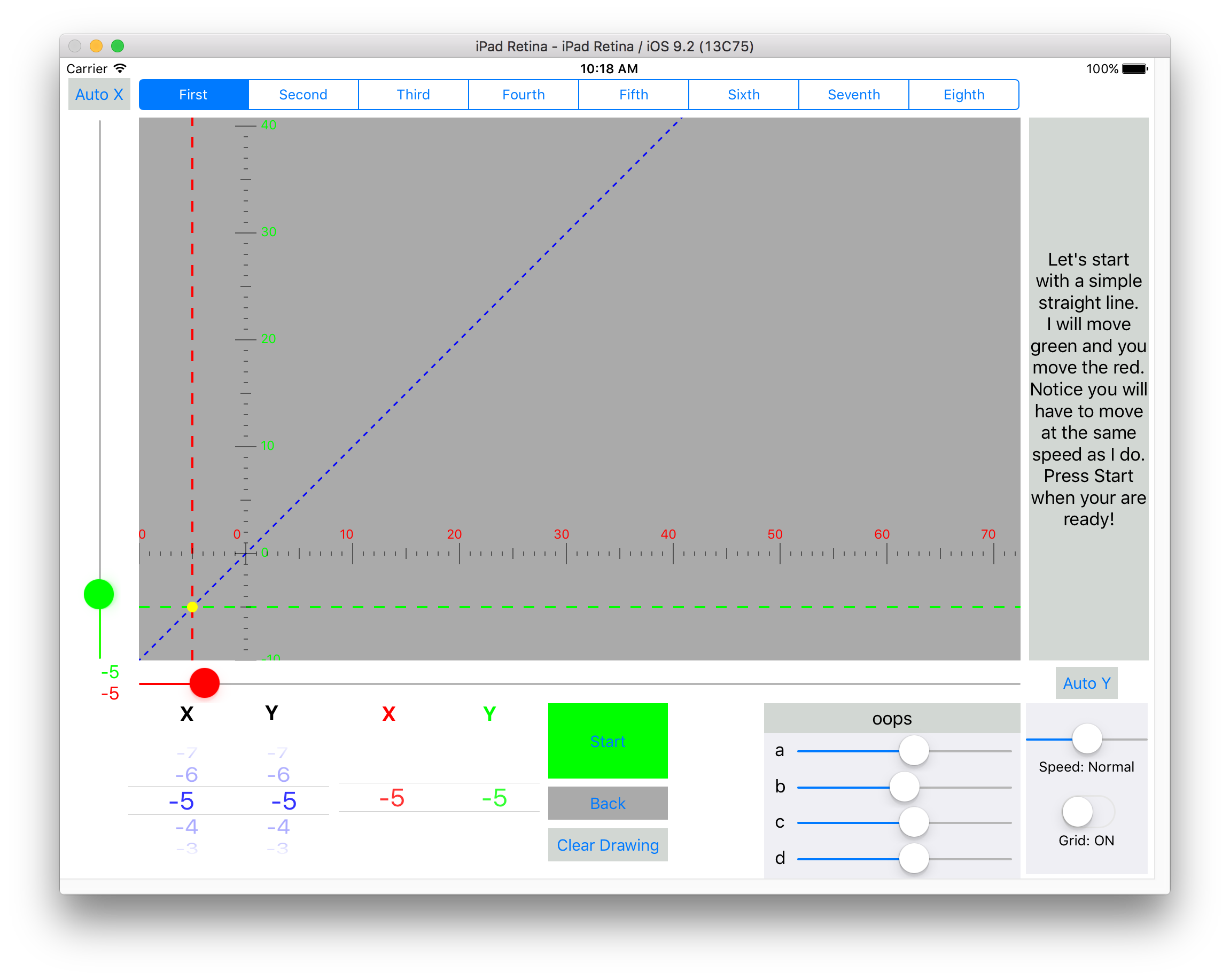

LDX will be a web-based tool which will overlay the existing LMS with the virtual student along with texts, images, and video triggered by analyzing the steps and content being published in the course. Let’s say that the user has published a 30 minute video – LDX might suggest that the video should be shorter. If the user publishes 50 pages of text with no images, LDX might suggest that images illustrate concepts more powerfully that text alone. LDX might prompt the user to insert a knowledge-check or reflection activity once the user has published 5 pieces of content. The idea is to provoke the user to think about how the learner will be processing the content towards learning.

The key features of LDX are:

- Virtual Student

- 3D character that talks to the user

- Guides the user through the process of creating the content

- Asks questions about the content and format of the course as it is created

- Course Publication Tool

- Curated Content

- Access to similar courses to get examples

- Ability to link to external material for student’s reference

EVIDENCE OF SUCCESS

I propose to assess the effectiveness of my solution by testing LDX with users with online teaching experience and users with no experience. The goals are to judge if such features improve the experience of creating the course and if the resulting course positively affects the learning outcomes. For practical purposes, I will narrow the content area to a beginner’s programming course at the undergraduate level since it is a subject matter I am familiar with and have access to potential users of the system.

APPENDIX A: TIME

Milestones and deliverables

When do you need to do what, in order to finish on time? Example:

| Winter quarter |

Observe target learners

Develop ideas

Write proposal |

| March 20, 2015 |

Proposal draft submitted to advisor |

| Date |

Participants for user testing and learning assessment arranged |

| Date |

Low-res learning assessments complete |

| Date |

Low-res prototype studies complete |

| Date |

Round 2 learning assessments complete |

| Date |

Round 2 prototype design complete |

| Date |

Final user testing and learning assessment complete |

| July 20, 20165 |

Project logo and video submitted |

| July 2931, 20165 |

EXPO presentation, demo |

| August 46, 20165 |

Draft report submitted |

| August 113, 20165 |

Signed Master’s Project Form submitted |

APPENDIX B: MONEY

| Item |

Approximate Cost |

| Virtual student – design |

$ 300 |

| Virtual student – development |

$ 3000 |

| Total: |

$3300� |

APPENDIX C: PEOPLE

Supporters

- Candace Thille – online teaching platform pedagogy

- Grace Lyo – VPTL – Associate Director of Instructional design

- Pedro Cunha – graphic design

- Eduardo Cremon – software architecture & development

- Karin Forssell & Paulo Blikstein – feedback & support�

APPENDIX D: SCHEDULE

| Month |

Day |

Item |

| February |

26 |

Define survey questions and send them out |

| March |

4 |

Define problem and target audience |

| March |

11 |

Collect Research |

| March |

18 |

Hot to measure success |

| March |

25 |

|

| April |

1 |

Feature list |

| April |

8 |

Feature list |

| April |

15 |

Wireframes |

| April |

22 |

Define technologies |

| April |

29 |

Database |

| May |

6 |

APIs |

| May |

13 |

User Interface |

| May |

20 |

User Interface |

| May |

27 |

User Interface |

| June |

3 |

Final Adjustments |

| June |

10 |

|

| June |

17 |

|

| June |

24 |

User Testing |

| July |

1 |

User Testing |

| July |

8 |

Analyze User Testing Data & Feedback |

| July |

15 |

Final Adjustments |

| July |

22 |

Final Adjustments |

| July |

29 |

V1 LDT Expo |

APPENDIX D: REFERENCES

Keywords

- Hybrid Online Learning

- Instructional Design

- Train the Trainer

- Professional Development

- TPCK & TPACK

Research / Citations

Essentials of Online Course Design https://www.routledge.com/products/9781138780163

Towards Best Practices in Online Learning and Teaching in Higher Education http://jolt.merlot.org/vol6no2/keengwe_0610.htm

EXPLORING FOUR DIMENSIONS OF ONLINE INSTRUCTOR ROLES: A PROGRAM LEVEL CASE STUDY https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0CB4QFjAAahUKEwjQ4te54tfIAhUL1GMKHcGSCxA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fonlinelearningconsortium.org%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fv9n4_liu_1.pdf&usg=AFQjCNHtnYf76HkFI-YrIcLhxBWoNPXhRw&sig2=RQVCKYoBJvqv-Gtu8oyCdw

(MY) THREE PRINCIPLES OF EFFECTIVE ONLINE PEDAGOGY http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ909855.pdf

Source Effects in Online Education http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/people/thies/las15-source-effects.pdf

The Five stage Model http://www.gillysalmon.com/five-stage-model.html

From face-to-face teaching to online teaching: Pedagogical transitions http://www.ascilite.org/conferences/hobart11/downloads/papers/Redmond-full.pdf

From On-Ground to Online: Moving Senior Faculty to the Distance Learning Classroom http://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/6/from-onground-to-online-moving-senior-faculty-to-the-distance-learning-classroom

Why some distance education programs fail while others succeed in a global environment http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1096751609000281

Case Study: Challenges and Issues in Teaching Fully Online Mechanical Engineering Courses http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-06764-3_74

TPCK and SAMR – Models for Enhancing Technology Integration (2008) http://www.msad54.org/sahs/TechInteg/mlti/SAMR.pdf

SAMR and TPCK in Action http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2017/08/28/SAMR_TPCK_In_Action.pdf

SAMR: Beyond the Basics http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2017/08/26/SAMRBeyondTheBasics.pdf

From the Classroom to the Keyboard: How Seven Teachers Created Their Online Teacher Identities http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/download/1814/3253

A structure equation model among factors of teachers’ technology integration practice and their TPCK http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131515000949

Examining Technopedagogical Knowledge Competencies of Teachers in Terms of Some Variables http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815006990/pdf?md5=1d1ccf6d1fb7088d7fda105f66d677c6&pid=1-s2.0-S1877042815006990-main.pdf

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge-practical (TPACK-Practical) model: Examination of its validity in the Turkish culture via structural equation modeling http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131515001189

Using TPCK as a scaffold to self-assess the novice online teaching experience http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01587919.2015.1019964#aHR0cDovL3d3dy50YW5kZm9ubGluZS5jb20vZG9pL3BkZi8xMC4xMDgwLzAxNTg3OTE5LjIwMTUuMTAxOTk2NEBAQDA=

What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge? http://www.editlib.org/p/29544/

The role of TPACK in physics classroom: case studies of preservice physics teachers http://ac.els-cdn.com/S187704281201779X/1-s2.0-S187704281201779X-main.pdf?_tid=cf1faf84-81bf-11e5-8938-00000aacb35f&acdnat=1446509831_08753d5dcf76ed3f790bd4382aae1e31

Handbook of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) for Educators https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=lEbJAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=tPCK&ots=-p0TWk4RCI&sig=FElDYqBq7xyKcFWehvVRZ91LrNE#v=onepage&q&f=false

When using technology isn’t enough: A comparison of high school civics teachers׳ TPCK in one-to-one laptop environments http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885985X14000229

Teacher Education Programs and Online Learning Tools: Innovations in Teacher http://www.igi-global.com/gateway/book/63882

A Blended-learning Pedagogical Model for Teaching and Learning EFL Successfully Through an Online Interactive Multimedia Environment https://journals.equinoxpub.com/index.php/CALICO/article/view/23157/19162

The Effectiveness of Online and Blended Learning: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature https://www.sri.com/sites/default/files/publications/effectiveness_of_online_and_blended_learning.pdf

How to Do More with Less: Lessons from Online Learning http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ982835.pdf

Build It But Will They Teach?: Strategies for Increasing Faculty Participation & Retention in Online & Blended Education http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer172/betts_heaston172.html

The design and development of an e-guide for a blended mode of delivery in a teacher preparation module http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/progress/progress_v36_n2_a6.pdf

Lessons from the virtual classroom : the realities of online teaching [2013] https://searchworks.stanford.edu/?q=836557457

Essentials for Blended Learning: A Standards-Based Guide http://www.lybrary.com/essentials-for-blended-learning-a-standardsbased-guide-p-412451.html

Design and development process for blended learning courses http://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1504/IJIL.2013.052900

Pearl Jacobs, The challenges of online courses for the instructor http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/131555.pdf

Developing an Online Course: Challenges and Enablers https://www.academia.edu/7511220/Developing_an_Online_Course_Challenges_and_Enablers

Considerations in Online Course Design http://ideaedu.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/idea_paper_52.pdf