This was a tough one… instructions and content were not very clear/cohesive.

Arquivo da categoria: Engineering Education

Engineering Education – Week 4.2 – Reading Notes

LOFT Process Guides: Understand Phase.

Techniques: Identify Problems, Preparation

- Identify problems

- What problems should the learners be able to solve?

- Subject matter expert develops list of challenging tasks

- Steps:

- Identify challenging tasks

- Learning environment will help learner do something they couldn’t do before

- Create problem typology

- List all the problems learner must be able to tackle

- Group problems into categories of similar knowledge and skills required

- Describe the problem

- Create problem statement

- Describe how it sits in the typology

- How is the problem solved

- What skills does it require

- Supporting materials

- Identify challenging tasks

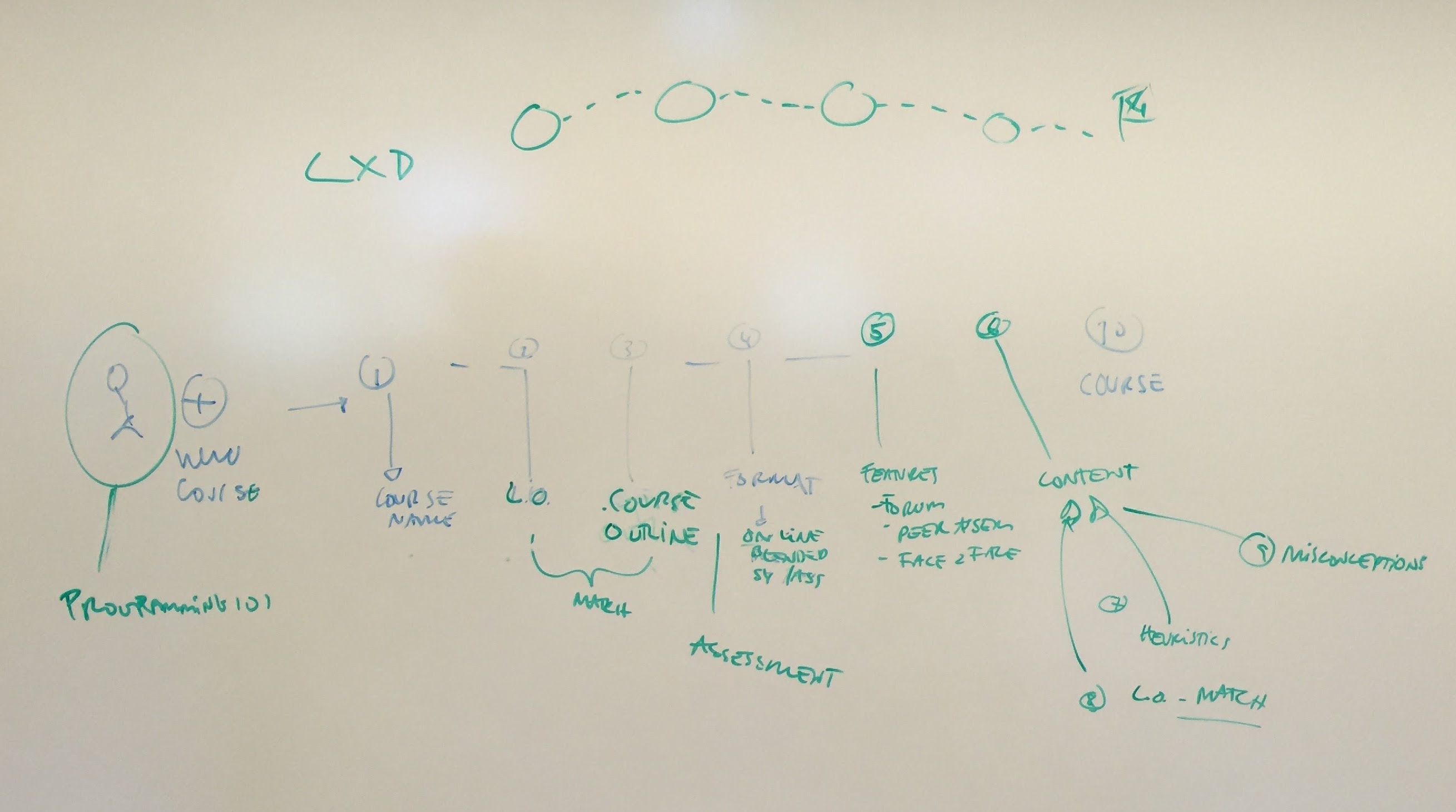

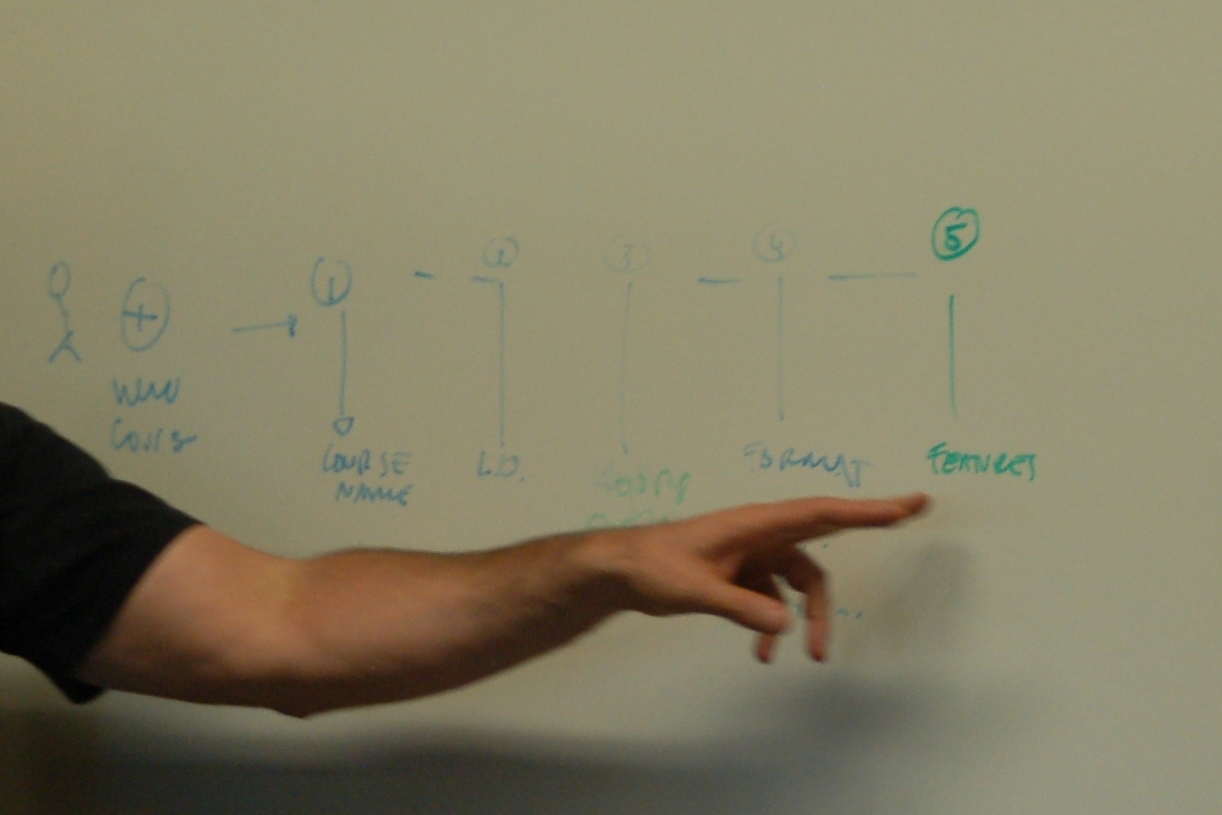

Presentation: Learning Module Design Understand Phase (benchmark tests and cognitive analysis)

- Cognitive task analysis – what specifically should be learned

- Workflow

- Identify experts

- Identify cognitively challenging tasks

- Gather data on how expert performs task

- Analyze data

- Represent it

- Steps

- What are the project deliverables?

- Identify what the stakeholders need (including the student of course)

- What is the task?

- Create a focus statement

- What aspects of expertise do you need to know about?

- How to identify expert performance?

- Documentation analysis (a.k.a. bootstrapping)

- Come in with a schema

- Go or no go?

- If documents describe it all, no need to do full CTA

- What situations will tell you the most about the issue?

- Identify experts

- Identify problems

- Choose CTA method

- Concept mapping

- Expert + facilitator + mapper

- Node and link diagram to map out concepts and relationships

- Verbal Protocol Analysis (VPA) / Talk-aloud problem solving (TAPS)

- Talk while solving a problem

- Code expert’s behavior: “verbal protocol”

- Guided Experiential Learning (GEL) CTA

- Interview one expert then validate with 2 other experts

- Critical Decision Method (CDM)

- Facilitator + note taker

- Interview in 4 sweeps

- Identify good incident story

- Chronology of good decisions

- Goals, expectations and cues in each decision

- Errors novices might make

- Percursor, Action, Result, Interpretation (PARI)

- Avionics training environments

- Experts are interview in pairs

- One tries to solve the problem

- Other expert runs the simulation

- Applied Cognitive Task Analysis (ACTA)

- Expert describes problem in 4-6 steps

- Describe what is difficult in each task

- Present expert with simulation and ask about:

- Actions

- Assessments

- Critical cues

- Erros

- Concept mapping

- Write your Preparation Report

- What are the project deliverables?

Engineering Education – Week 4.2 – Game Critique Assignment

Engineering Education – Week 4.1 – Class Notes

Great class today talking about game design balancing…

Engineering Education – Week 4.1 – Reading Notes

Reading:

Jesse, S. (2008). The Art of Game Design. A book of Lenses.

Chapter 11 – Game Mechanics Must be in Balance

Summary:

This article furthers my awe of game development. It must be one of the hardest things to do well. I know from experience that the skills, time, and planning needed to program a game is leaps and bounds more complex than to program a mobile app or a web site. I also know that the graphics, which in most case have to be moving, are of extreme importance in a game. Again, it seems much harder to do art for games than to do art for a magazine, website, or mobile app. Then you have the storyline, the game mechanics, and all the factors mentioned in this article. This article is obviously assuming that you already have developed a game that can be balanced. I keep thinking of all the planning, design, development, and testing that goes on when creating a game. Obtaining balance is already hard in life; now try doing that in a game!

Notes:

The Twelve Most Common Types of Game Balance

- Fairness

- Symmetrical Games

- All players have equal powers.

- Random assignment resolves small potential asymmetries

- Asymmetrical Games

- Simulate real-world situations: it’s not symmetric

- Ways to explore the game-space: customize characters and strategies

- Personalization: shape game to suit their skill level

- Level playing field: opponent car’s must go slower at first

- Interesting situations: provocations, stimulate curiosity

- Example: Biplane Battle

- Choose from 3 planes with speed, maneuverability, and firepower

- Can balance on numbers alone but must play-test them to really feel it

- Takes around 6 months to balance your game properly

- Example: Rock Paper Scissors

- None of the elements are supreme

- Lens of Fairness

- Should my game be symmetrical? Why?

- Should my game be asymmetrical? Why?

- Which is more important: that my game is a reliable measure of who has the most skill, or that it provide an interesting challenge to all players?

- If I want players of different skill levels to play together, what means will I use to make the game interesting and challenging for everyone?

- Symmetrical Games

- Challenge vs. Success

- Strategies

- Increase difficulty with each success

- Let player get through the easy parts first

- Create “layer of challenge”

- Let players choose the difficulty level

- Play-test with a variety of players

- Don’t make it impossible to win

- Lens of Challenge

- What are the challenges in my game?

- Are they too easy, too hard, or just right?

- Can my challenges accommodate a wide variety of skill levels?

- How does the level of challenge increase as the player succeeds?

- Is there enough variety in the challenges?

- What is the maximum level of challenge in my game?

- Strategies

- Meaningful Choices

- Bad choices

- 50 equal vehicles to choose from = no choice at all

- A choice no-one wants

- Dominant strategy

- One option might win over all others – not good – need to adjust balance

- If Choices > Desires, then the player is overwhelmed.

- If Choices < Desires, the player is frustrated.

- If Choices = Desires, the player has a feeling of freedom and fulfillment.

- Lens of Choices

- What choices am I asking the player to make?

- Are they meaningful? How?

- Am I giving the player the right number of choices? Would more make them feel more powerful? Would less make the game clearer?

- Are there any dominant strategies in my game?

- Triangularity

- Choices

- Play it safe -> small reward

- Big risk -> big reward

- “Balanced asymmetric risk”

- Lens

- Do I have triangularity now? If not, how can I get it?

- Is my attempt at triangularity balanced? That is, are the rewards commensurate with the risks?

- Choices

- Bad choices

- Skill vs. Chance

- Lens of Skill vs. Chance

- Are my players here to be judged (skill), or to take risks (chance)?

- Skill tends to be more serious than chance: Is my game serious or casual?

- Are parts of my game tedious? If so, will adding elements of chance enliven them?

- Do parts of my game feel too random? If so, will replacing elements of chance with elements of skill or strategy make the players feel more in control?

- Lens of Skill vs. Chance

- Head vs. Hands

- Hard to balance and some games have both

- Lens

- Are my players looking for mindless action, or an intellectual challenge?

- Would adding more places that involve puzzle-solving in my game make it more interesting?

- Are there places where the player can relax their brain, and just play the game without thinking?

- Can I give the player a choice — either succeed by exercising a high level of dexterity, or by finding a clever strategy that works with a minimum of physical skill?

- If “1” means all physical, and “10” means all mental, what number would my game get?

- This lens works particularly well when used in conjunction with Lens #16: Lens of the Player.

- Competition vs. Cooperation

- Animal urges

- Most games are competitive in nature

- Collaborate to compete against machine

- Collaborate to compete against another team

- Lens of Competition

- Does my game give a fair measurement of player skill?

- Do people want to win my game? Why?

- Is winning this game something people can be proud of? Why?

- Can novices meaningfully compete at my game?

- Can experts meaningfully compete at my game?

- Can experts generally be sure they will defeat novices?

- Lens of Cooperation

- Cooperation requires communication. Do my players have enough opportunity to communicate? How could communication be enhanced?

- Are my players friends already, or are they strangers? If they are strangers, can I help them break the ice?

- Is there synergy (2 + 2 = 5) or antergy (2 + 2 = 3) when the players work together? Why?

- Do all the players have the same role, or do they have special jobs?

- Cooperation is greatly enhanced when there is no way an individual can do a task alone. Does my game have tasks like that?

- Tasks that force communication inspire cooperation. Do any of my tasks force communication?

- Lens of Competition vs. Cooperation

- If “1” is Competition and “10” is Cooperation, what number should my game get?

- Can I give players a choice whether to play cooperatively or competitively?

- Does my audience prefer competition, cooperation, or a mix?

- Is team competition something that makes sense for my game? Is my game more fun with team competition, or with solo competition?

- Short vs. Long

- Determined by win or loose conditions

- Timing is everything

- Lens

- What is it that determines the length of my gameplay activities?

- Are my players frustrated because the game ends too early? How can I change that?

- Are my players bored because the game goes on for too long? How can I change that?

- Setting a time limit can make gameplay more exciting. Is it a good idea for my game?

- Would a hierarchy of time structures help my game? That is, several short rounds that together comprise a larger round?

- Rewards

- Types

- Praise: good job

- Points: the more the merrier

- Prolonged play: keep going

- Gateway: access to a new level

- Spectacle: usually paired with other types of reward

- Expression: change clothes, decorate… fun

- Powers: more

- Resources: more

- Completion: I did it

- Rules of thumb

- People get acclimated to rewards

- Variable rewards

- Lens

- What rewards is my game giving out now? Can it give out others as well?

- Are players excited when they get rewards in my game, or are they bored by them? Why?

- Getting a reward you don’t understand is like getting no reward at all. Do my players understand the rewards they are getting?

- Are the rewards my game gives out too regular? Can they be given out in a more variable way?

- How are my rewards related to one another? Is there a way that they could be better connected?

- How are my rewards building? Too fast, too slow, or just right?

- Types

- Punishment

- Reasons to punish

- Creates endogenous value: resources are more valuable if they can be taken away

- Taking risks is exciting

- Increases challenge

- Types

- Shaming: “you loose”

- Loss of points: very painful

- Shortened play: loose a life

- Terminated play: game over

- Setback: go to last checkpoint

- Removal of Powers: slow down

- Resource depletion: loss of goods

- Better to reward than punish

- Punishments need to be understood and preventable – risk of being “unfair”

- Lens

- What are the punishments in my game?

- Why am I punishing the players? What do I hope to achieve by it?

- Do my punishments seem fair to the players? Why or why not?

- Is there a way to turn these punishments into rewards and get the same, or a better effect?

- Are my strong punishments balanced against commensurately strong rewards?

- Reasons to punish

- Freedom vs. Controlled Experience

- Game isn’t a simulation of real life, rather more interesting

- Too much freedom becomes cumbersome

- Take control over experience when necessary – no problem

- Simple vs. Complex

- Kinds of complexity

- Innate complexity: too many rules or “exception cases” – hard to learn

- Emergent complexity: simple rules with complex situations – hard to achieve in the design of the game

- Lens of Complexity

- What elements of innate complexity do I have in my game?

- Is there a way this innate complexity could be turned into emergent complexity?

- Do elements of emergent complexity arise from my game? If not, why not?

- Are there elements of my game that are too simple?

- Neutral vs. Artificial Balancing

- Careful when adding innate complexity to balance game

- Elegance

- Game is simple to learn and understand, but full of emergent complexity

- Pac Man: short- and long-term goals for player, slow down when eating, points measure success

- Lens of Elegance

- What are the elements of my game?

- What are the purposes of each element? Count these up to give the element an “elegance rating.”

- For elements with only one or two purposes, can some of these be combined into each other, or removed altogether?

- For elements with several purposes, is it possible for them to take on even more?

- Character

- Having a personality is a good thing (Tower of Pisa)

- Lens of Character

- Is there anything strange in my game that players talk about excitedly?

- Does my game have funny qualities that make it unique?

- Does my game have flaws that players like?

- Kinds of complexity

- Detail vs. Imagination

- “The game is not the experience — games are simply structures that engender mental models in the mind of the player.” (Jesse, 2008)

- How to do it well

- Only detail what you can do well

- Let the imagination do the heavy lifting

- Subtitles for example

- Give details the imagination can use

- Help imagination grasp the functionality of the game, making it more accessible

- Familiar words do not need much detail

- Use the binocular effect

- Show the details first to situate the user

- Give details that inspire imagination

- Only detail what you can do well

- Lens of Imagination

- What must the player understand to play my game?

- Can some element of imagination help them understand that better?

- What high-quality, realistic details can we provide in this game?

- What details would be low quality if we provided them? Can imagination fill the gap instead?

- Can I give details that the imagination will be able to reuse again and again?

- What details I provide inspire imagination?

- What details I provide stifle imagination?

Game Balancing Methodologies

- Use the Lens of the Problem Statement.

- Doubling and halving.

- “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” – William Blake, Proverbs of Hell

- Double or half values to see the effects

- Train your intuition by guessing exactly

- Document your model

- Tune your model as you tune your game

- Plan to balance

- Let the players do it

Balancing Game Economies

- Defined by:

- How will I earn money?

- How will I spend money I have earned?

- Balancing act:

- Fairness

- Challenge

- Choices

- Chance

- Cooperation

- Time

- Rewards

- Punishment

- Freedom

- Lens of Economy

- How can my players earn money? Should there be other ways?

- What can my players buy? Why?

- Is money too easy to get? Too hard? How can I change this?

- Are choices about earning and spending meaningful ones?

- Is a universal currency a good idea in my game, or should there be specialized currencies?

Dynamic Game Balancing

- Adjust difficulty level on the fly

- It spoils the reality of the world

- It is exploitable

- Players improve with practice

The Big Picture

- Lens of Balance

- Does my game feel right? Why or why not?

Engineering Education – Week 3 – Ed Tech Critique Assignment

![]()

Engineering Education – Week 3.2 – Class Notes

Talked about Learning Module Design, the Understand Phase (benchmark tests and initial cognitive analysis).

Engineering Education – Week 3 – Group Meeting

Met with James and Camila about this class’ final project – which will be my Master’s project. Discussed what were the interventions I imagined we could do with the instructors and we all seemed to agree with what could be done.

While we were in the meeting, we were ‘visited’ by a photographer who wanted to take some pictures of the classroom we were in.

Later on I received an email from her 🙂

Hello,

Yesterday I wandered into a classroom and took a couple of pictures of you talking about course design. I work at Stanford in the VPGE office, and I also (on the side) write a blog about graduate education. I am working on a post related to a newly released study about the value of teaching development activities for grad students (lsfss.wceruw.org). My blog is here: http://gradlogic.org

I wanted to know whether it was ok to use one of these photos. Your face isn’t shown. I may also want to use them later, but only if it is ok with you.

Thanks,

Chris M. Golde

chris@golde.org

GRAD | LOGIC blog

Helping graduate students navigate the ups and downs of graduate school

http://gradlogic.org

Engineering Education – Week 3.1 – Class Notes

Reading:

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Summary:

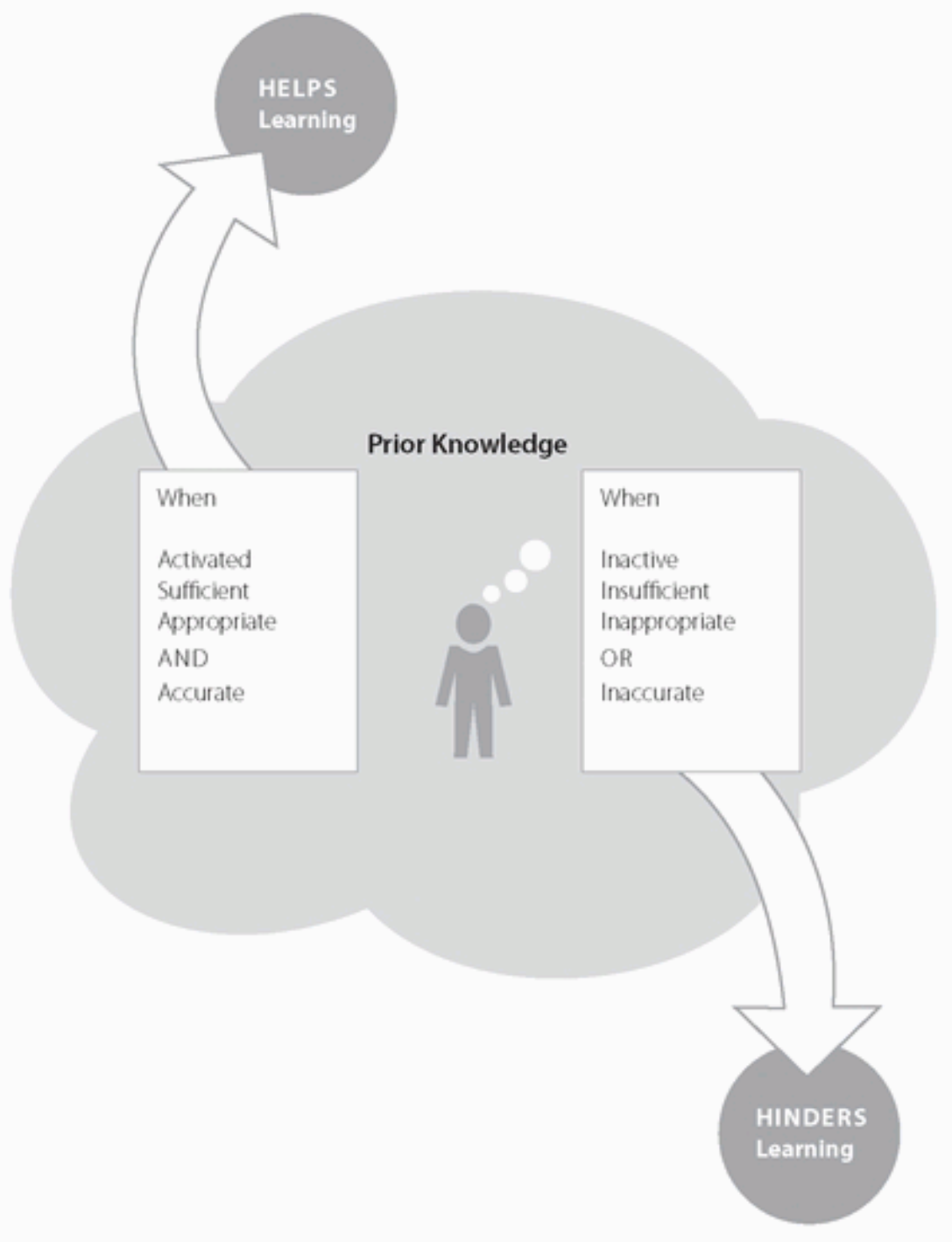

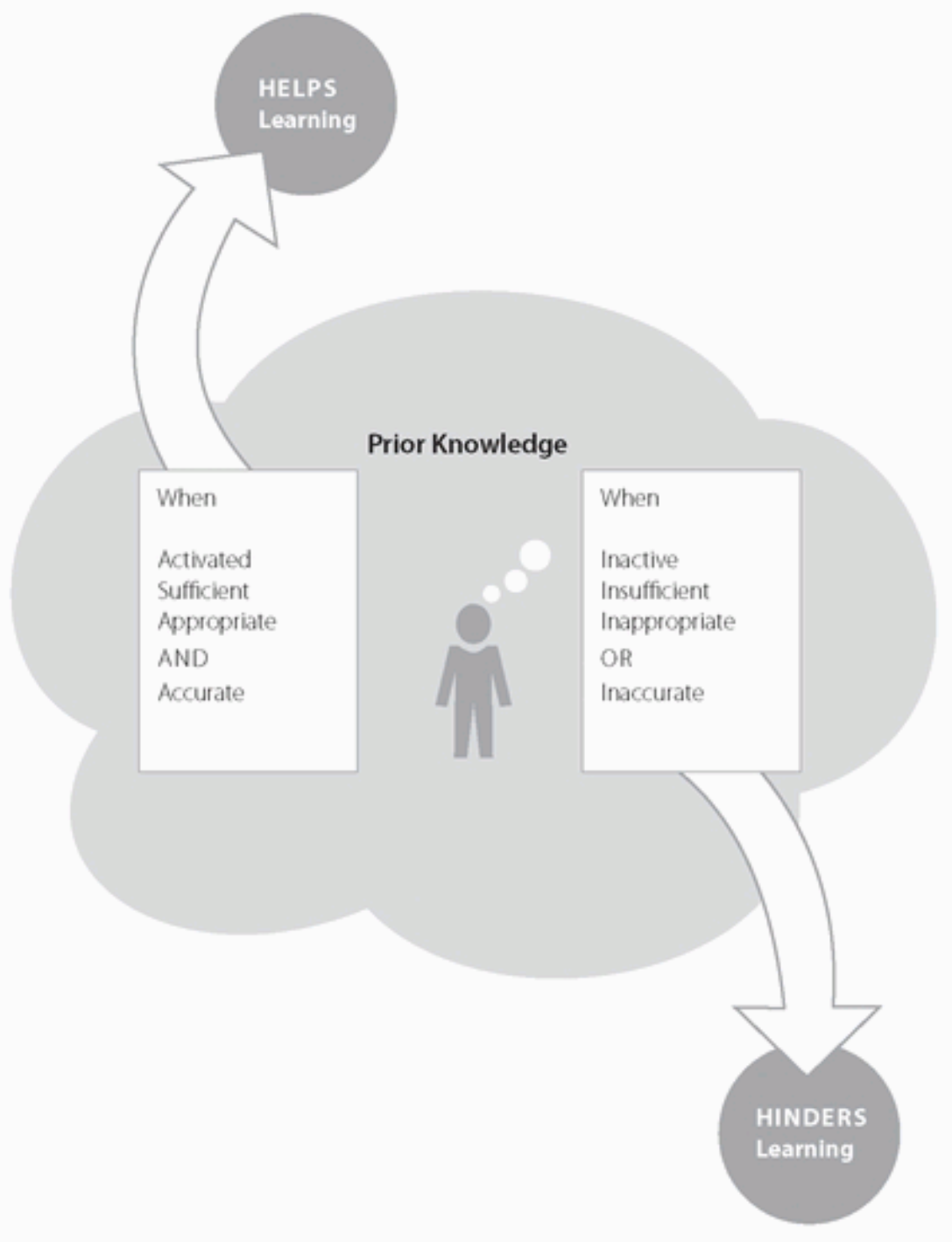

The first chapter illustrates how Prior Knowledge can affect learning both positively and negatively. When dealing with counterituitive concepts especially, common misconceptions that root from inacurate Prior Knowledge, are very hard to change and require time, cognitive energy, and an attentive teacher to scaffold the process. I appreciated all the methods offered to gauge, activate, recognize, and suplement Prior Knowledge as well as correct inacurate Prior Knowlege.

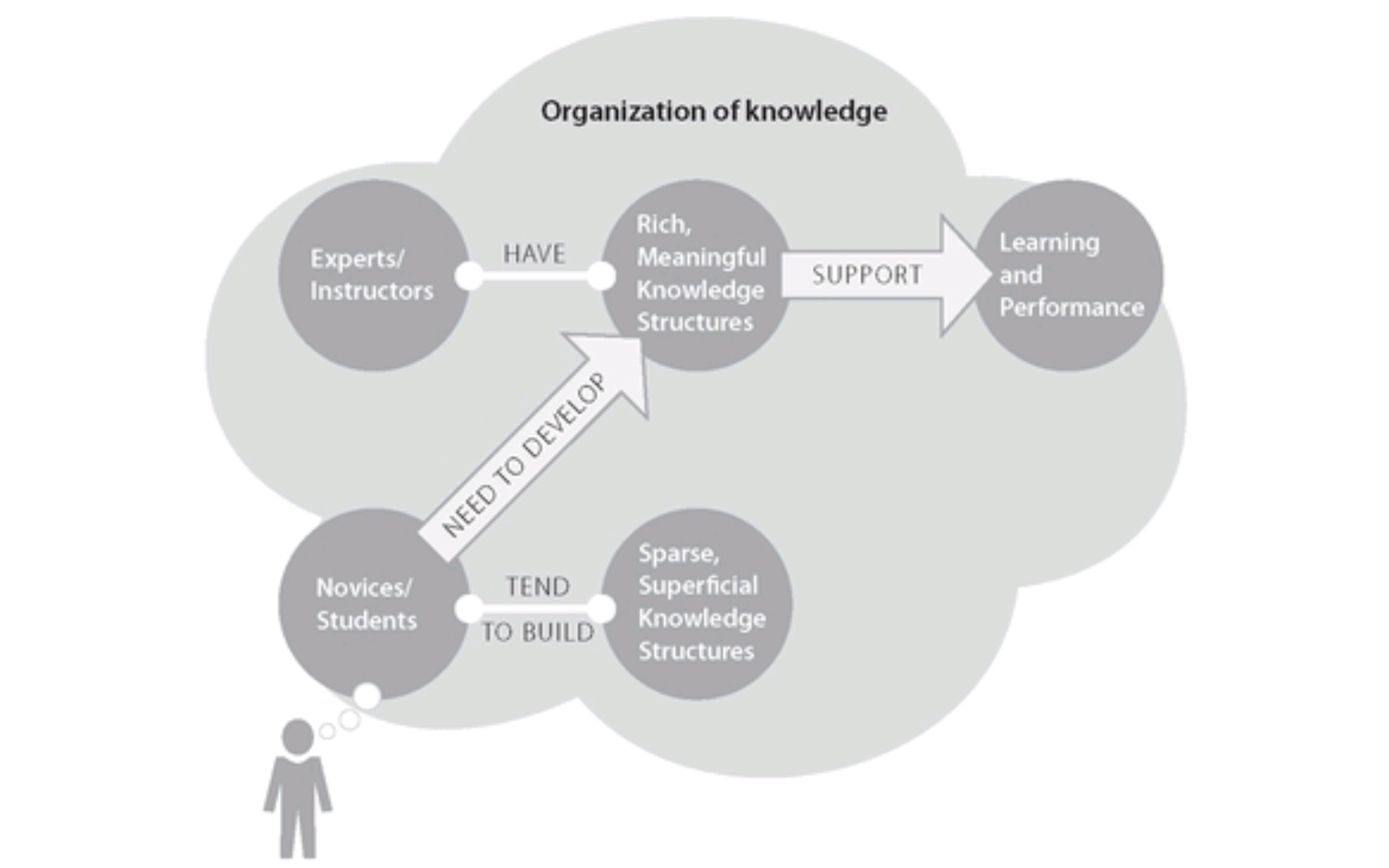

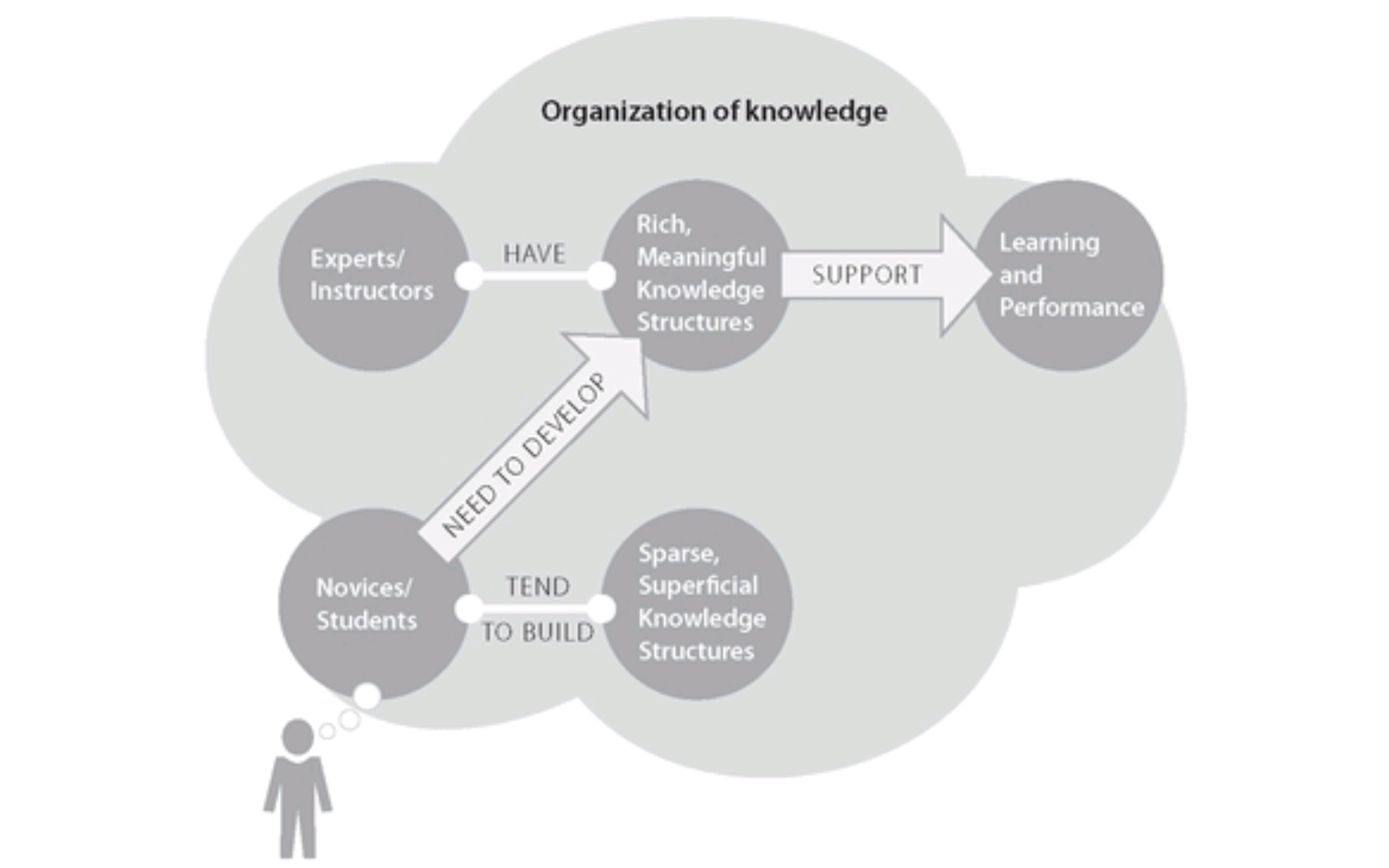

The second chapter goes into how students organize knowledge and how might a teacher build these schemas more effectively on them. It is important for the teacher to realize that students come into a new subject area with shallow understanding of how apparently unconnected peices of knowledge relate to each other. This richness of connections is one of the abilities that makes someone an expert. Therefore, the more the teacher is able to demonstrate how to build these connections and organize the information in an effective manner, the more students might learn.

“…it is not just what you know but how you organize what you know that influences learning and performance. ” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

Notes:

Chapter 1 – How Does Student’s Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning?

- Principle: Students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder learning.

- Help to make connections

- Hinder with misconceptions that carry forward

- “If they do not draw on relevant prior knowledge—in other words, if that knowledge is inactive—it may not facilitate the integration of new knowledge. Moreover, if students’ prior knowledge is insufficient for a task or learning situation, it may fail to support new knowledge, whereas if it is inappropriate for the context or inaccurate, it may actively distort or impede new learning” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- “If they do not draw on relevant prior knowledge—in other words, if that knowledge is inactive—it may not facilitate the integration of new knowledge. Moreover, if students’ prior knowledge is insufficient for a task or learning situation, it may fail to support new knowledge, whereas if it is inappropriate for the context or inaccurate, it may actively distort or impede new learning” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- Activating Prior Knowledge

- Teacher must probe and activate knowledge from the student – simply mentioning it sometimes already does the trick

- “In other words, with minor prompts and simple reminders, instructors can activate relevant prior knowledge so that students draw on it more effectively (Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Dooling & Lachman, 1971).” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- Teacher must probe and activate knowledge from the student – simply mentioning it sometimes already does the trick

- Accurate but Insufficient Knowledge

- Declarative Knowledge

- Recite facts

- Procedural Knowledge

- How to do it

- You can have one and not the other, and vice-versa

- Declarative Knowledge

- Inappropriate Prior Knowledge

- Knowledge that hinders understanding of “counterintuitive” concepts

- Teachers must attend to:

- Explain conditions and contexts of applicability

- Abstract principles with multiple examples and contexts

- Analogies – differences and similarities

- Activate prior knowledge to strengthen appropriate associations

- Inacurate Prior Knowledge

- Misconceptions

- Extremely hard to correct

- Require greater cognitive energy

- Conceptual changes occur over time

- Bridging

- Concepts that act as intermediaries between misconception and desired concepts

- Misconceptions

- Methods

- Gauge the Extent and Nature of Students’ Prior Knowledge

- Talk to colleagues

- Diagnostic assessments

- Short, low-stakes assessments

- Quiz or essay

- At the beginning

- Concept inventories

- Reveal common misconceptions

- Students assess own Prior Knowledge

- Cursory familiarity: “I have heard of the term”

- Factual knowledge: “I could define it”

- Conceptual knowledge: “I could explain it to someone else”

- Application: “I can use it to solve problems”

- Brainstorming to reveal Prior Knowledge

- Concept map activity

- Patterns of error in student work

- Activate accurate Prior Knowledge

- Exercises to generate students’ Prior Knowledge

- can generate inaccurate and inappropriate as well as accurate and relevant knowledge

- Link new material to materials in other courses

- Link new material to materials in your own course

- Analogies and examples to link to Everyday Knowledge

- Reason on the basis of Prior Knowledge

- Exercises to generate students’ Prior Knowledge

- Insufficient Prior Knowledge

- Identify Prior Knowledge you expect students to have

- Remediate insufficient Prerequisite Knowledge

- Recognize Inappropriate Prior Knowledge

- Conditions of applicability

- Heuristics to avoid inappropriate application of knowledge

- Identify discipline-specific conventions

- Show where analogies break down

- Correct Inacurate Knowledge

- Students to make and test predictions

- Justify their reasoning

- Opportunities to use accurate knowledge

- Allow sufficient time

- Gauge the Extent and Nature of Students’ Prior Knowledge

Chapter 2: How Does the Way Students Organize Knowledge Affect Their Learning?

- Principle: How students organize knowledge influences how they learn and apply what they know.

- Teach students how to organize content as experts do

- Form fits function

- The way you organize knowledge affects how you apply knowledge

- “we need to provide students with appropriate organizing schemes or teach them how to abstract the relevant principles from what they are learning.” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- Strategies:

- Reveal and enhance knowledge organization

- Concept maps of your own

- Associate tasks with organizations

- Show organization of course, lectures, lab, or discussions

- Contrasting and boundary cases to highlight organization features

- Deep features – make them explicit

- Explicitly make connections

- Work with multiple organization structures

- Concept maps that show student’s knowledge organizations

- Sorting tasks that show student’s knowledge organizations

- Monitor student’s work

- Reveal and enhance knowledge organization

- “…it is not just what you know but how you organize what you know that influences learning and performance. ” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

Engineering Education – Week 3.1 – Reading Summary

Reading:

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Summary:

The first chapter illustrates how Prior Knowledge can affect learning both positively and negatively. When dealing with counterituitive concepts especially, common misconceptions that root from inacurate Prior Knowledge, are very hard to change and require time, cognitive energy, and an attentive teacher to scaffold the process. I appreciated all the methods offered to gauge, activate, recognize, and suplement Prior Knowledge as well as correct inacurate Prior Knowlege.

The second chapter goes into how students organize knowledge and how might a teacher build these schemas more effectively on them. It is important for the teacher to realize that students come into a new subject area with shallow understanding of how apparently unconnected peices of knowledge relate to each other. This richness of connections is one of the abilities that makes someone an expert. Therefore, the more the teacher is able to demonstrate how to build these connections and organize the information in an effective manner, the more students might learn.

“…it is not just what you know but how you organize what you know that influences learning and performance. ” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

Notes:

Chapter 1 – How Does Student’s Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning?

- Principle: Students’ prior knowledge can help or hinder learning.

- Help to make connections

- Hinder with misconceptions that carry forward

- “If they do not draw on relevant prior knowledge—in other words, if that knowledge is inactive—it may not facilitate the integration of new knowledge. Moreover, if students’ prior knowledge is insufficient for a task or learning situation, it may fail to support new knowledge, whereas if it is inappropriate for the context or inaccurate, it may actively distort or impede new learning” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- “If they do not draw on relevant prior knowledge—in other words, if that knowledge is inactive—it may not facilitate the integration of new knowledge. Moreover, if students’ prior knowledge is insufficient for a task or learning situation, it may fail to support new knowledge, whereas if it is inappropriate for the context or inaccurate, it may actively distort or impede new learning” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- Activating Prior Knowledge

- Teacher must probe and activate knowledge from the student – simply mentioning it sometimes already does the trick

- “In other words, with minor prompts and simple reminders, instructors can activate relevant prior knowledge so that students draw on it more effectively (Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Dooling & Lachman, 1971).” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- Teacher must probe and activate knowledge from the student – simply mentioning it sometimes already does the trick

- Accurate but Insufficient Knowledge

- Declarative Knowledge

- Recite facts

- Procedural Knowledge

- How to do it

- You can have one and not the other, and vice-versa

- Declarative Knowledge

- Inappropriate Prior Knowledge

- Knowledge that hinders understanding of “counterintuitive” concepts

- Teachers must attend to:

- Explain conditions and contexts of applicability

- Abstract principles with multiple examples and contexts

- Analogies – differences and similarities

- Activate prior knowledge to strengthen appropriate associations

- Inacurate Prior Knowledge

- Misconceptions

- Extremely hard to correct

- Require greater cognitive energy

- Conceptual changes occur over time

- Bridging

- Concepts that act as intermediaries between misconception and desired concepts

- Misconceptions

- Methods

- Gauge the Extent and Nature of Students’ Prior Knowledge

- Talk to colleagues

- Diagnostic assessments

- Short, low-stakes assessments

- Quiz or essay

- At the beginning

- Concept inventories

- Reveal common misconceptions

- Students assess own Prior Knowledge

- Cursory familiarity: “I have heard of the term”

- Factual knowledge: “I could define it”

- Conceptual knowledge: “I could explain it to someone else”

- Application: “I can use it to solve problems”

- Brainstorming to reveal Prior Knowledge

- Concept map activity

- Patterns of error in student work

- Activate accurate Prior Knowledge

- Exercises to generate students’ Prior Knowledge

- can generate inaccurate and inappropriate as well as accurate and relevant knowledge

- Link new material to materials in other courses

- Link new material to materials in your own course

- Analogies and examples to link to Everyday Knowledge

- Reason on the basis of Prior Knowledge

- Exercises to generate students’ Prior Knowledge

- Insufficient Prior Knowledge

- Identify Prior Knowledge you expect students to have

- Remediate insufficient Prerequisite Knowledge

- Recognize Inappropriate Prior Knowledge

- Conditions of applicability

- Heuristics to avoid inappropriate application of knowledge

- Identify discipline-specific conventions

- Show where analogies break down

- Correct Inacurate Knowledge

- Students to make and test predictions

- Justify their reasoning

- Opportunities to use accurate knowledge

- Allow sufficient time

- Gauge the Extent and Nature of Students’ Prior Knowledge

Chapter 2: How Does the Way Students Organize Knowledge Affect Their Learning?

- Principle: How students organize knowledge influences how they learn and apply what they know.

- Teach students how to organize content as experts do

- Form fits function

- The way you organize knowledge affects how you apply knowledge

- “we need to provide students with appropriate organizing schemes or teach them how to abstract the relevant principles from what they are learning.” (Ambrose et al., 2010)

- Strategies:

- Reveal and enhance knowledge organization

- Concept maps of your own

- Associate tasks with organizations

- Show organization of course, lectures, lab, or discussions

- Contrasting and boundary cases to highlight organization features

- Deep features – make them explicit

- Explicitly make connections

- Work with multiple organization structures

- Concept maps that show student’s knowledge organizations

- Sorting tasks that show student’s knowledge organizations

- Monitor student’s work

- Reveal and enhance knowledge organization

- Conclusion:

- “…it is not just what you know but how you organize what you know that influences learning and performance. ” (Ambrose et al., 2010)