“Whether it comes after teaching, while teaching, or by teaching, we often think of assessment as something done to students, not with them.” (Coffey, 2003, p.76)

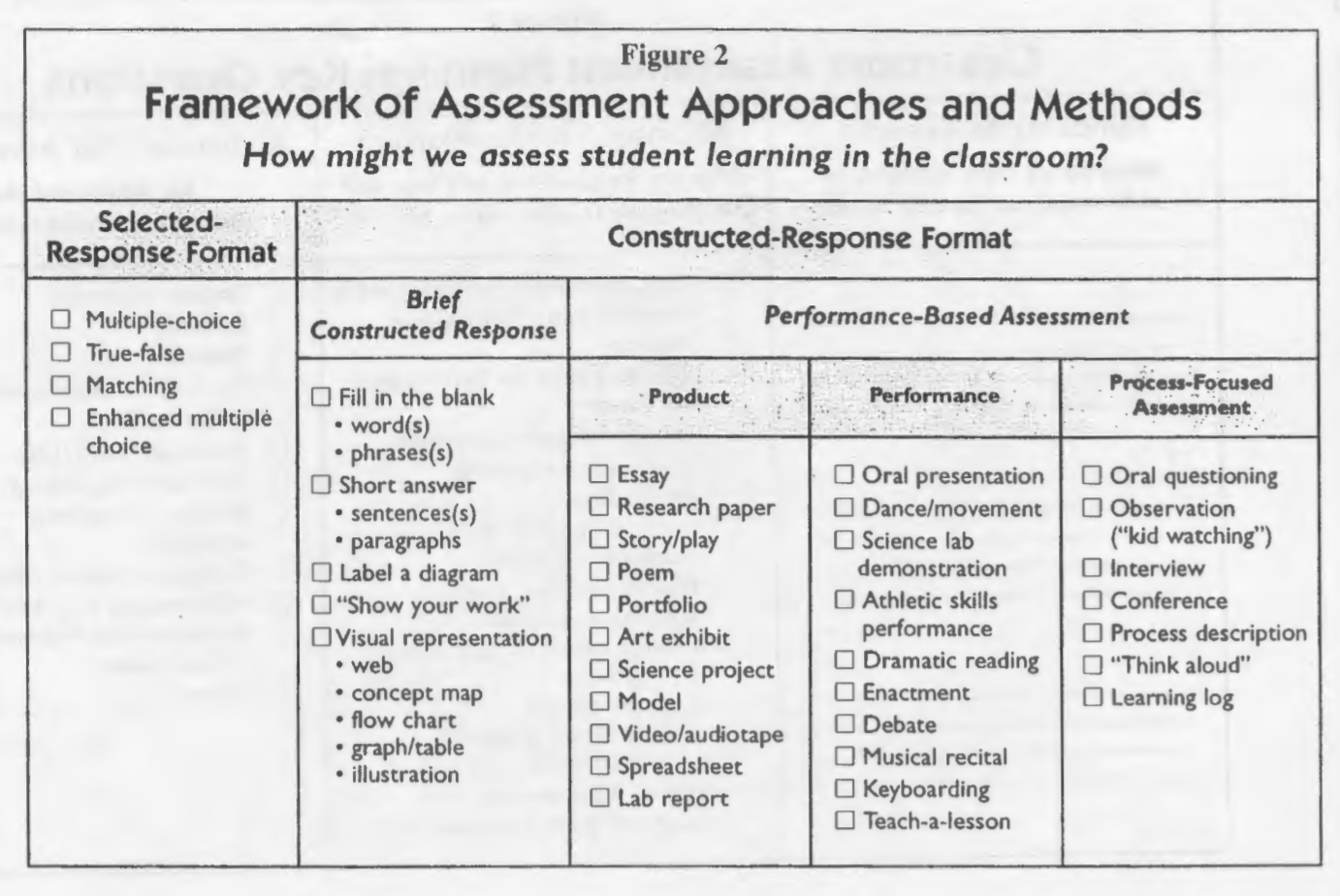

The word “assessment” is often thought of as the final grade on the report card or as standardized tests that simply rank or classify the student. What it should be thought of is an opportunity for learning and an integral part of classroom activities. In an evolved, mature, and structured teacher-student dynamic, students can create their own quizzes or exam questions, engage in reflections upon their peers presentations or projects, and even grade each other’s tests. The idea might sound radical yet the benefits might outweigh the extra work and planning it might take to ‘flip’ assessment. Being able to understand what quality work is, analyze your own work, receive feedback and act upon it, is a valuable life-long skill.

“When students play a key role in the assessment process they acquire the tools they need to take responsibility for their own learning.” (Coffey, 2003, p.77)

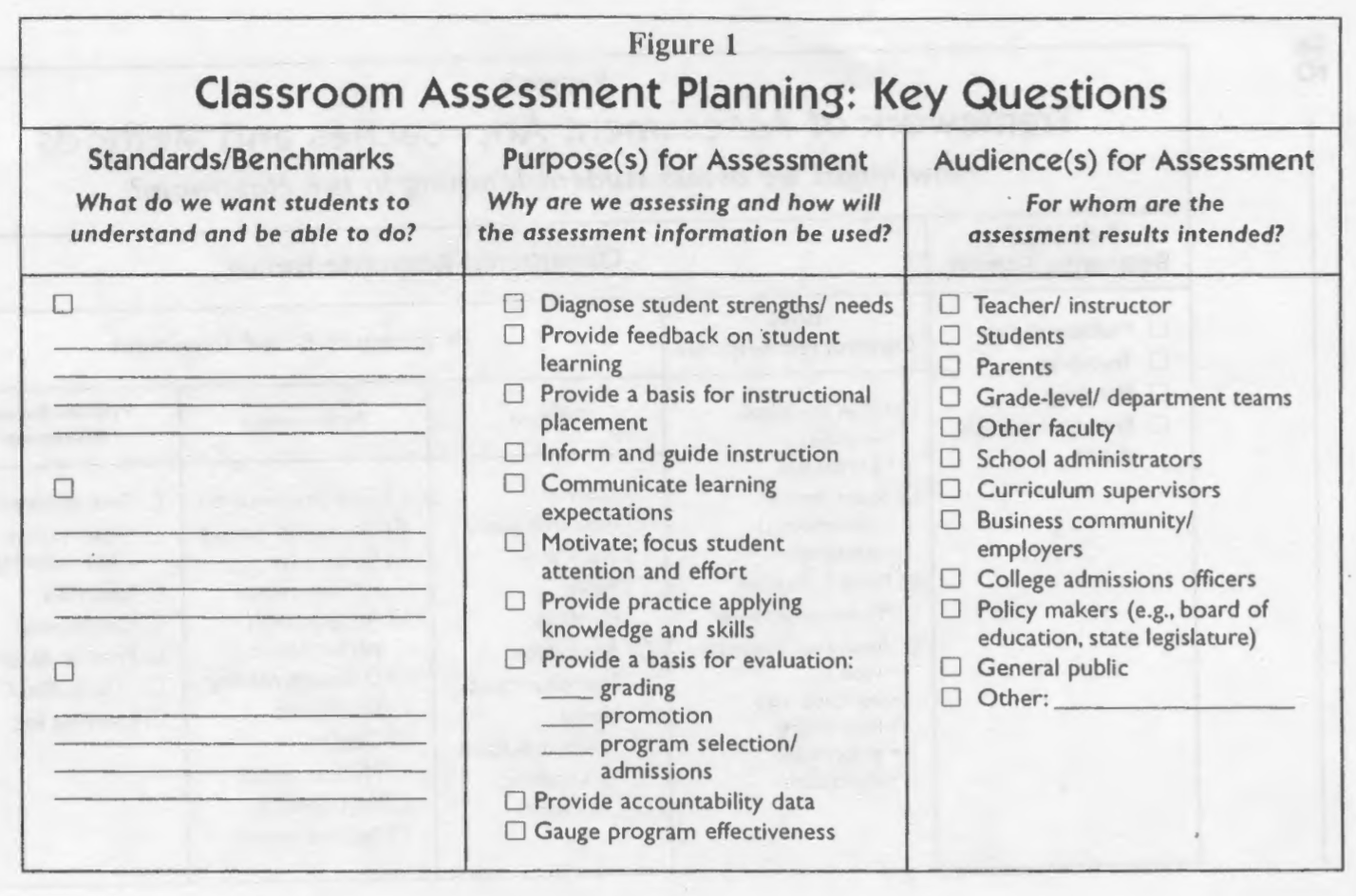

One of the main purpose of assessment is for external accountability but it’s best application might be to improve student motivation, curiosity for learning, and to improve the teacher’s efficacy. It is primordial for students to understand the purpose of their own education and to feel responsible for it. Exposing the students to how they will be assessed and what the enduring understandings the courses will bring to them gives them a sense of purpose of their education. Not knowing why you should learn math or science transforms the whole learning experience meaningless. This disconnect is minimized when the teacher starts by involving the students in creating measures and activities that will demonstrate their understanding of what the course is all about.

“Through the students’ explicit participation in all aspects of assessment activity, they arrived at shared meaning of quality work. Teachers and students used assessment to construct the bigger picture of an area of study, concept, or subject mater area.” (Coffey, 2003, p.78)

To apply this in a classroom requires a significant change in teaching practice. It might feel that engaging the students in everyday assessment practices takes precious time out of regular ‘content-coverage’. Yet this very engagement creates for the students, connections between content and demonstration of knowledge, between their own work and what quality work looks like. It might even make the teacher’s work easier in the sense that the students create their own tests and even grade their own work. They also provide feedback to their peers during presentations and in the process are learning by engaging with the material. Buy-in from school administrators also should be easy since you can actually use traditional assessments in this process. The topic of large scale assessment in itself is an interesting topic students should be aware of, understand the reasons why they exist, and reduce the stress involved in test taking; but I digress.

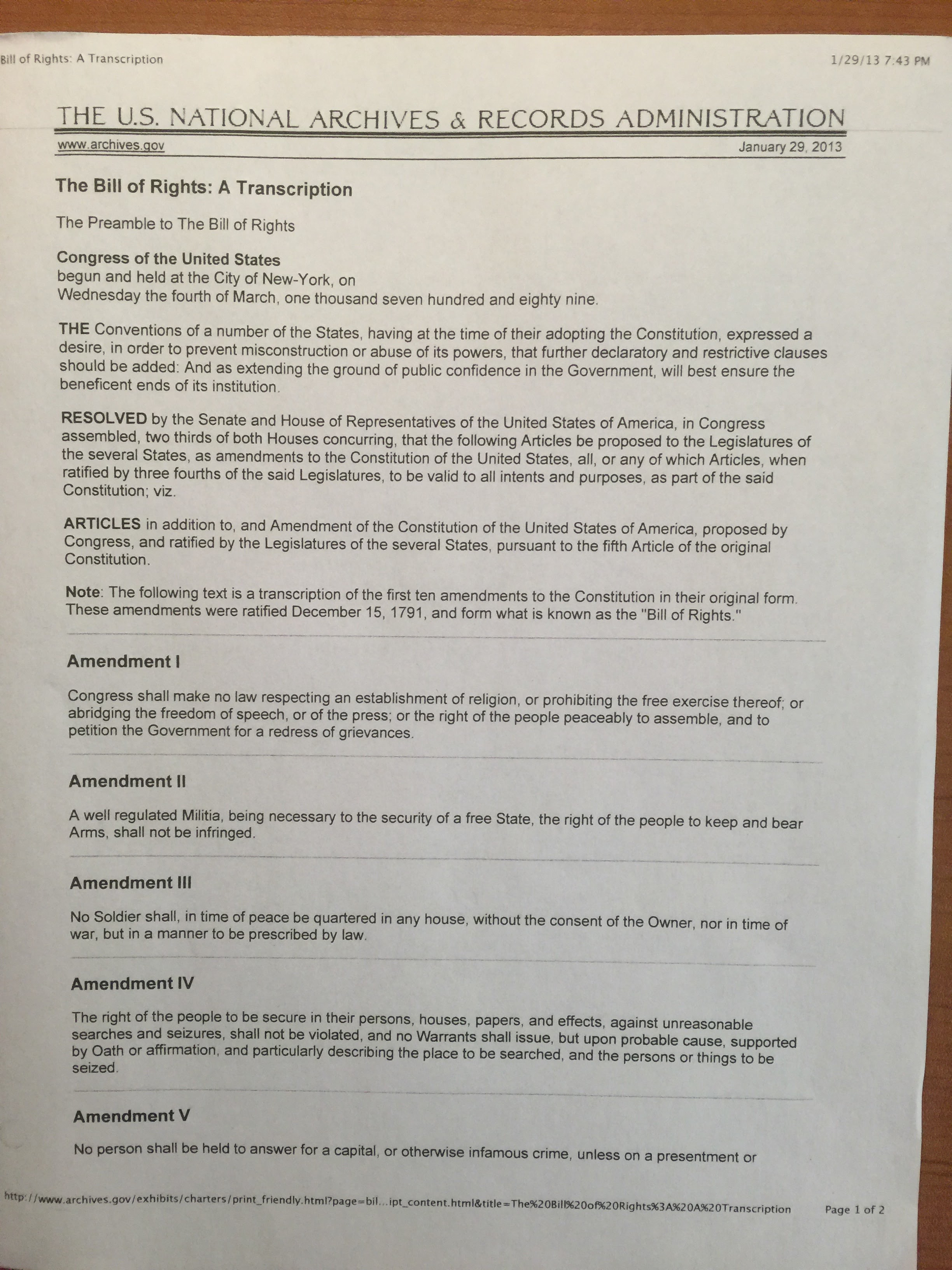

So how might you apply this concept in practice? Coffey’s concept of “everyday assessment” fits in well with Wiggins and McTighe’s (2005) Understanding by Design process. The main twist or difference would be that the process of determining acceptable evidence of student understanding would not be done in isolation, but with the students. The teacher would obviously have to provide the course’s goals and essential questions but will do so in a manner that students understand why it is important to their lives (present and future) and how will they know if they actually learned the content.

“Despite initial resistance, as students learned assessment-related skills, demarcations between roles and responsibilities with respect to assessment blurred. They learned to take on responsibilities and many even appropriated ongoing assessment into their regular habits and repertoires.” (Coffey, 2003, p.86)

The process is not easy and it takes time but it provides a sense of clarity for the teacher when planning a course or a lesson. It’s not about the content that has to be delivered, it’s about creating mechanisms that demonstrate student’s learning. It’s about reviving that child’s desire to show-off to their parents what they have just accomplished. It’s about knowing what your parents expect of you and creating a relationship that is based upon growth.

References

Coffey, J. (2003). Involving Students in Assessment. In J. Atkin & J. Coffey (Eds.) Everyday Assessment in the Science Classroom. Arlington, VA: National Science Teachers Association. pp. 75-87.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding By Design. (Expanded 2nd edition) Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. pp. 13-34, and 105-133.