Reading:

Ambrose, S. A. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Notes:

Chapter 4 – “How Do Students Develop Mastery?”

- A Sum of Their Parts

- Students perform better on individual projects rather than in group projects

- May not poses the team work skills

- “Shouldn’t They Know This by Now?”

- Seems like the students do not learn anything from previous courses!

- May never have put previous knowledge into practice

- Whole is greater than the sum of the parts

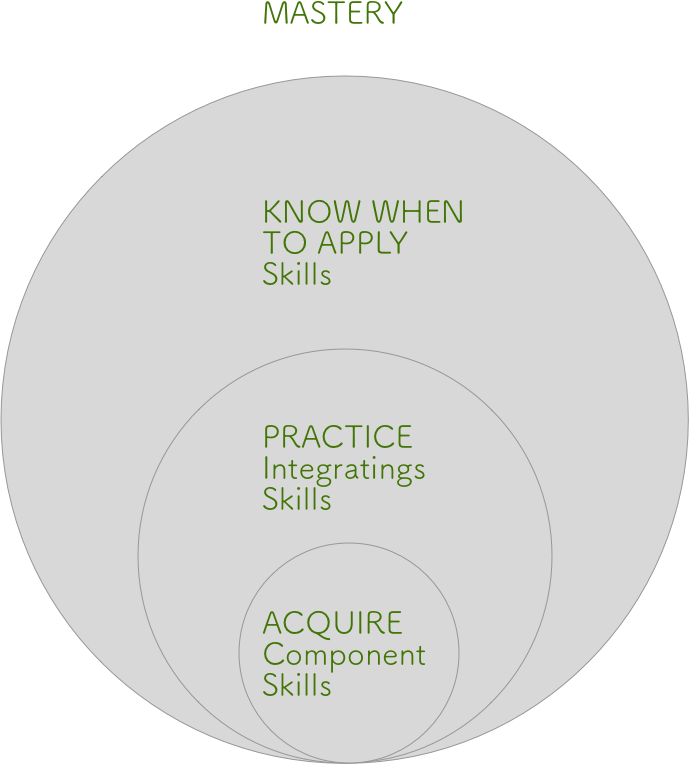

- “Principle: To develop mastery, students must acquire component skills, practice integrating them, and know when to apply what they have learned.”

- Expertise – liability for teaching sometimes

- Elements of Mastery

- Acquire – direct instruction

- Practice – interact with content

- When to Apply – project based learning

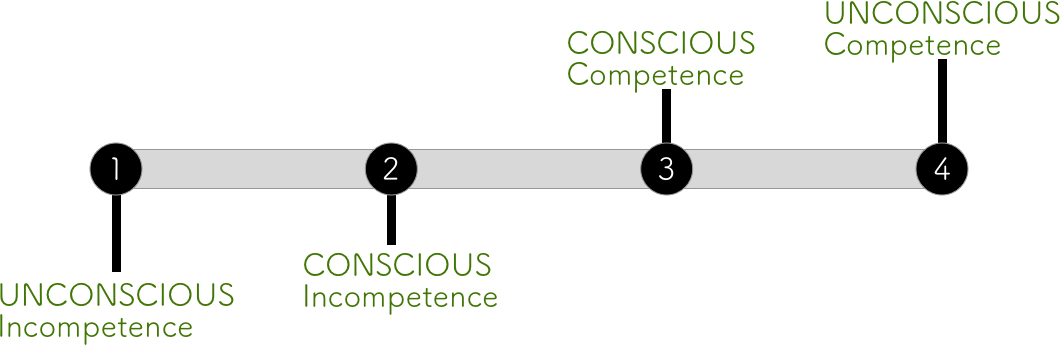

- Stages in the Development of Mastery

- Unconscious Incompetence

- Does not recognize what needs to be learned. Do not know what they do not know.

- Conscious Incompetence

- Know what needs to be learned

- Conscious Competence

- Still have to think about what they’ve mastered

- Unconscious Competence

- They just do it instinctively. Forget how much they know.

- Unconscious Incompetence

- Expert’s Blind Spot

- “When expert instructors are blind to the learning needs of novice students, it is known as expert blind spot (Nickerson, 1999; Hinds, 1999; Nathan & Koedinger, 2000; Nathan & Petrosino, 2003). To get a sense of the effect of expert blind spot on students, consider how master chefs might instruct novice cooks to “sauté the vegetables until they are done,” “cook until the sauce is a good consistency,” or “add spices to taste.”” (Ambrose, 2010)

- “instructors must be able to “unpack” or decompose complex tasks.” (Ambrose, 2010)

- Problem solving strategies, not rote procedural tasks

- Scaffolding (worked-example effect)

- Reduce student’s cognitive load by providing some help and thus freeing up resources for learning

- Transfer

- Apply skills learned in one context onto a novel context

- Near -> Far Transfer (the central goal of education!?)

- Similar -> Dissimilar contexts

- Extremely hard. Research shows very little evidence.

- “a) transfer occurs neither often nor automatically, and (b) the more dissimilar the learning and transfer contexts, the less likely successful transfer will occur. ” (Ambrose, 2010)

- Overspecificity – context dependence

- Associate skill with context too tightly

- Mason Spencer & Weisberg, 1986; Perfetto, Bransford, & Franks, 1983

- Some positive research

- Throwing darts onto a target under water

- When presented with the concepts of refraction, students did better

- “Divide and conquer” in a military example

- Only were able to apply strategy to a medical problem when explicitly told to do so.

- Throwing darts onto a target under water

- Strategies to “teach for transfer”

- Decompose complex tasks

- Combine and integrate skills

- Learn to identify where to apply what they learned

- Techniques

- Push Past Your ® Expert Blind Spot

- “What would students have to know—or know how to do—in order to achieve what I am asking of them?”

- Enlist TAs or Graduate students for task decomposition

- You might have unconscious competence while they would have conscious competence making it clearer where further unpacking or decomposing complex tasks

- Talk to your colleagues

- Compare notes, research papers, oral presentations, or design projects.

- Enlist help from someone outside your discipline

- They will not have your expert blindspots and may add to your repertoire of teaching strategies.

- Explore available educational materials

- You may just find that other’s have already faced the same challenges you are facing

- Focus student’s attention on key aspects of the task

- Do not overload them cognitively with empty information

- Diagnose weak or missing component skills

- Evaluate previous knowledge early on to be able to adjust

- Provide isolated practice of weak or missing skills

- Create extra assignments and activities to supply deficits

- Give students practice to increase fluency

- Engage with the content to produce artifacts that will reinforce the link between theory and practice

- Temporarily constrain the scope of the task

- Use smaller tasks and build up into more complex tasks

- Explicitly include integration in your performance criteria

- Integration is a skill itself

- Discuss conditions of applicability

- Explicitly mention where you might apply the learnings

- Apply skills or knowledge in diverse contexts

- Use multiple cases to evidence transfer

- Generalize to larger principles

- Step back from the details to relate them to macro phenomena

- Use comparisons to identify deep features

- Surface features vs deep features

- Specify context and ask students to identify relevant skills or knowledge

- Give a case study and ask students to generate knowledge and skills appropriate for that context.

- Specify skills and knowledge and ask students to identify contexts in which they apply

- Students need to think where else could they apply what they’ve just learned.

- Provide prompts to relevant knowledge

- Create knowledge bridges: “Think back…”, “Remember we talked about…”

- Push Past Your ® Expert Blind Spot

Chapter 5 – “What Kinds of Practice and Feedback Enhance Learning?”

- Cases

- “When practice does not make perfect”

- Students may keep doing things the wrong way… maybe the problem is with the instruction and not the students

- If students do not posses the prerequisite skills or knowledge, very rarely they will be able to perform in any manner above the base.

- Have to allow for time and practice – cannot change the activity’s flavor until student’s get it…

- “They just do not listen!”

- Students are not always clear of what is expected of them. Must model by showing what quality work looks like.

- “When practice does not make perfect”

- Practice and feedback

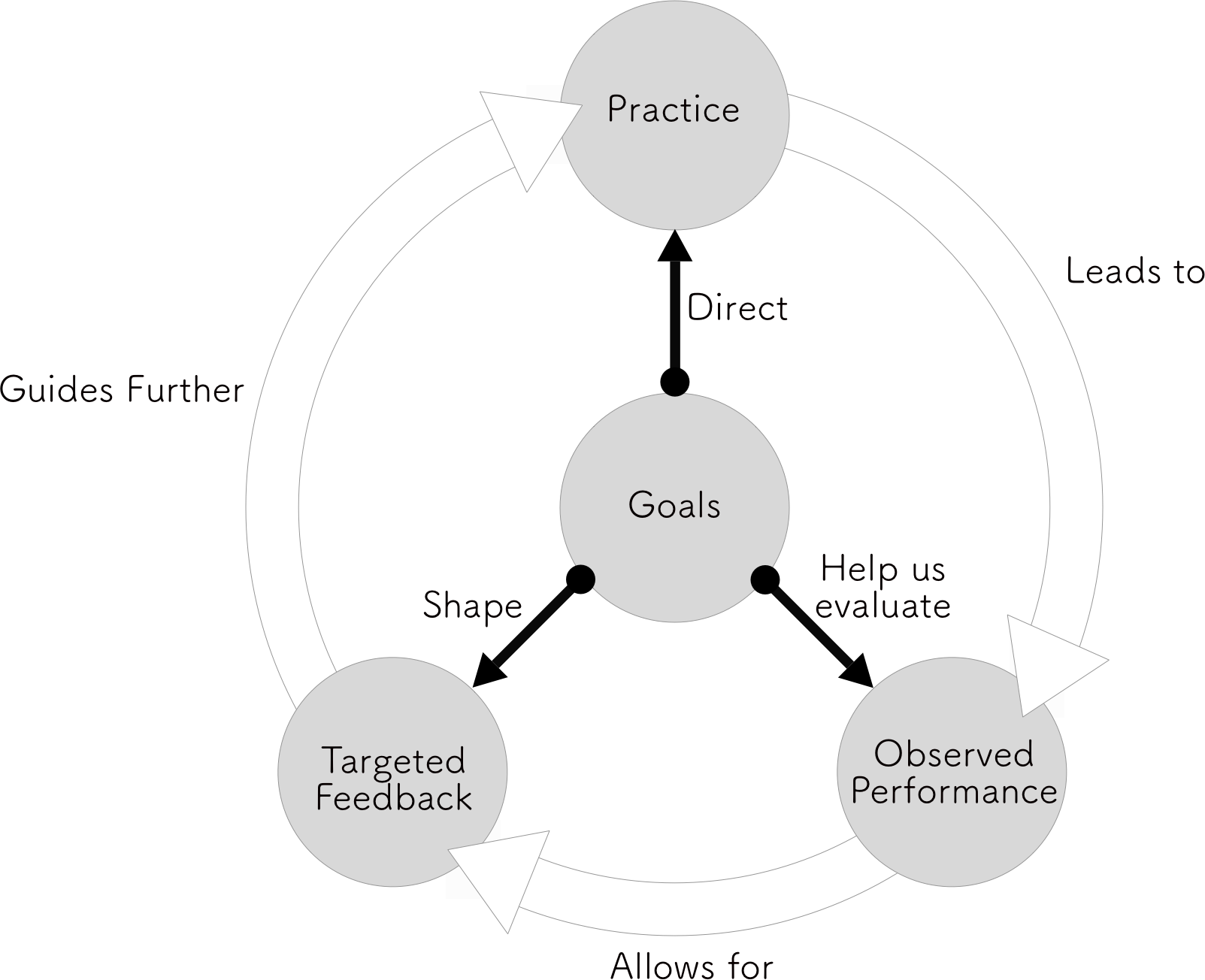

- “Principle: Goal-directed practice coupled with targeted feedback are critical to learning.” (Ambrose, 2010)

- Characteristics of successful practice:

- Focuses on a specific goal or criterion for performance

- Deliberate practice towards goals

- If student is not clear on what the goal is, it is hard to achieve it.

- Targets an appropriate level of challenge relative to students’ current performance

- If the task is too hard, students will be overwhelmed and not be able to take away much from the task

- ZPD… has to be proximal

- Similar to balancing in video games: not too hard, not too easy

- Is of sufficient quantity and frequency to meet the performance criteria

- Time and quantity

- Focuses on a specific goal or criterion for performance

- “Overall, the implications of the body of research on practice are that to achieve the most effective learning, students need sufficient practice that is focused on a specific goal or set of goals and is at an appropriate level of challenge. ” (Ambrose, 2010)

- Goal-directed feedback + targeted feedback

- What they do or don’t understand

- Where their performance is

- How they should direct their efforts

- More formative, less summative feedback

- Don’t over do it though – let the student grapple with it for a bit

- Must consider how much time to give feedback to all and amount of time needed to process all the feedback by the students.

- Feedback must:

- Focus students on key concepts you want them to learn

- Time and frequency depends on when the student will be able to use it

- Linked to additional practice opportunities

- Goal Directed Practice strategies

- Assess previous knowledge to adjust challenge level

- Be explicit about goals in course material

- Use rubric with students to specify and communicate the performance criteria

- Provide multiple opportunities for practice

- Scaffold assignments

- Set expectations about practice

- Show what target performance is

- Show what you do not want

- Refine goals and performance criteria as the course progresses

- Targeted Feedback strategies

- Look for patterns or errors in student work

- Prioritize your feedback

- Balance strengths and weaknesses on your feedback

- Design frequent opportunities to give feedback

- Provide feedback at the group level

- Incorporate peer feedback

- Require students to specify how they used feedback in subsequent work